Early detection of skin cancer and especially of melanoma is essential to effective treatment. Delays in melanoma treatment can harm prognoses and cost lives. Yet delays are rising for American patients, with wait lists for dermatologists particularly lengthy. An obvious solution is to help improve skin cancer detection ‘upstream,’ closer to a patient’s first point of contact with the medical system: their primary care provider (PCP).

In this post, we’ll look closer at just why that’s a good idea, talk about what skin cancer detection looks like in America and around the world today, and posit how PCPs can help improve skin cancer care for their patients.

Skin cancer detection in primary care: the value

The value of skin cancer detection in primary care is two-fold. First, more patients engage with a primary care provider than with a dermatologist. Bundling skin cancer checks of suspicious lesions with yearly physicals makes sense from a detection standpoint on those grounds alone. Additionally, most patients who are referred to a dermatologist are referred by a PCP.

Second, and equally important, early detection, diagnosis and treatment are crucial to the successful management of skin cancer, and what the Greater Access for Patients Partnership (GAPP) calls ‘America’s dermatology wait times crisis’ is an impediment to timely diagnosis. (GAPP includes The American Health Quality Association, The Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants, and the Melanoma Research Alliance, among many others.)

Across American healthcare, specialist referrals are a lengthy process, averaging 26 days in 2022. This is an 8% increase from 2017 and a 14% increase on 2004’s figure. Americans are now waiting longer for all specialist referrals than ‘they have been since we began conducting the survey,’ in the words of Tom Florence, president of AMN Healthcare physician search division. Like most broad statistics, though, that one hides outliers. Orthopedic surgery referrals average a wait time of 16.9 days, but the national average wait time for a dermatology appointment is 34.5 days, up from an average of 32.4 days wait in a major US metro area in 2017. This varies by geography: in Portland, Oregon, the average is 84 days, while in Philadelphia it is just nine days.

Lengthy delays are not merely a matter of subjective patient satisfaction. They directly affect prognosis.

Add to this the fact that the majority of skin cancers in America are detected not by any medical professional but by the patient, and the wait time for an initial appointment must be added to the wait time for referral. In contrast to specialist referrals, wait times for PCPs have fallen across America since 2017, from 29.3 days to 20.6 days; but that could still leave a patient in Portland waiting over 100 days to have their skin cancer accurately diagnosed before treatment can begin. For many patients, this is a long period of worry and uncertainty.

(Source) Superficial spreading melanoma, under dermatoscopy.

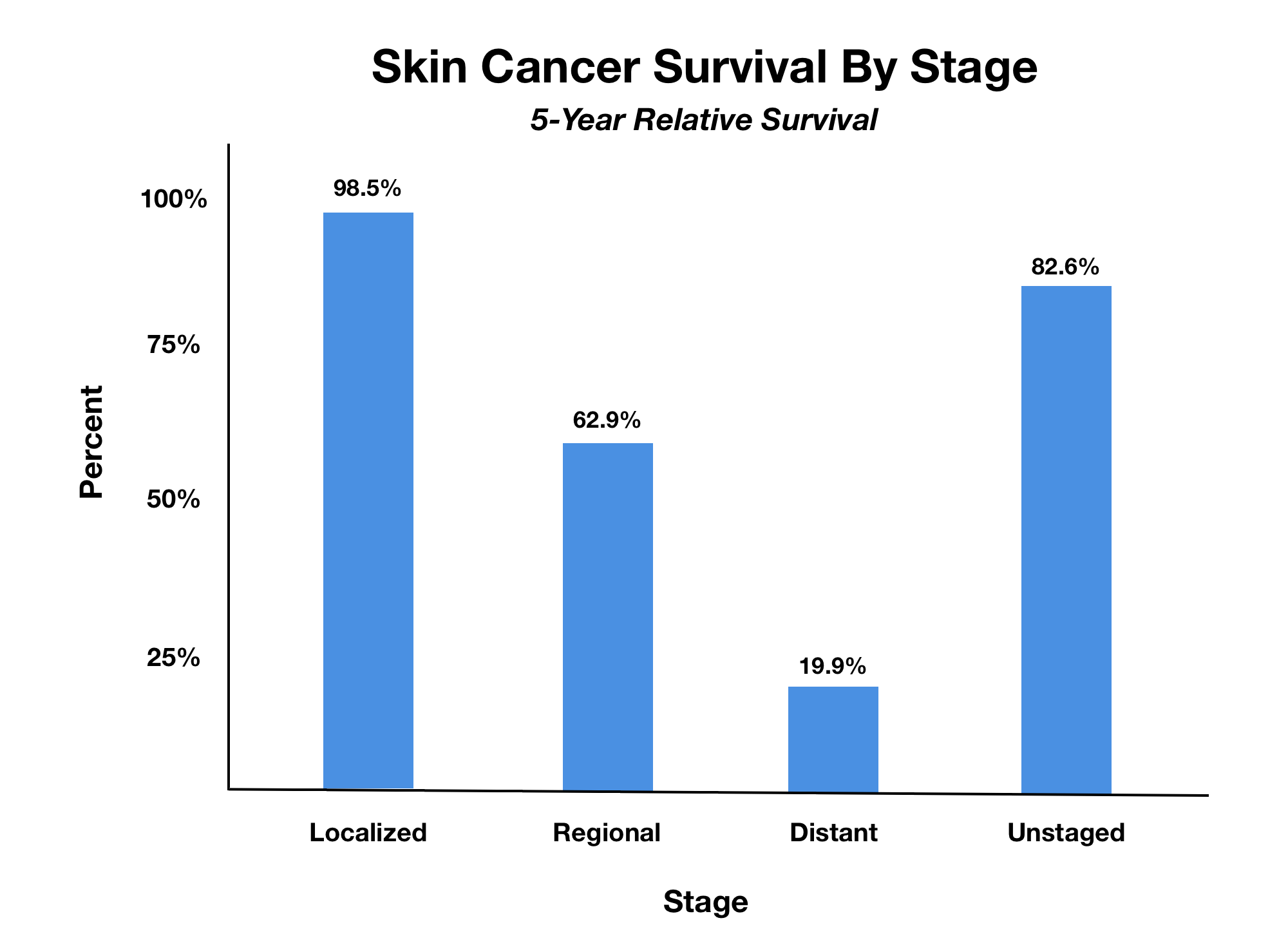

For melanoma in particular, delays are deadly. Melanomas account for just 10% of all skin cancers but are the fifth most common form of cancer in America. Treatment is extremely time-sensitive. When brain tumors are excluded, the five-year survival rate for all cancers in the US from 2011-2017 was 53–68%. For melanomas detected and treated before spreading to the lymph nodes, it is 99%. But a melanoma can spread beyond its original tumor site to become life-threatening in as little as six weeks — just 42 days, less than halfway through our imaginary Oregonian’s Portland wait time.

The five-year survival rate for melanomas that have metastasized to lymph nodes is 68% — about the American norm for all cancers, but a drop of a third from in situ tumors. The survival rate for melanomas that have spread to distant lymph nodes and organs is between 30% and 18%.

(Source) Skin cancer survival rates by stage. Because it progresses rapidly, timing is crucial in melanoma prognosis.

In a six-year study using data drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program‚ ‘treatment delays of 3 to 5 months were associated with worse MSM [Melanoma-Specific Mortality] and any delay beyond 1 month was associated with worse OM [Overall Mortality],’ with negative effects particularly concentrated in patients with early-stage tumors.

Remember — patients don’t know whether their suspicious mole or blemish is melanoma or not, and the advance from stage 0–II melanomas to far more deadly stage III–IV tumors can take less time than the wait for a dermatologist’s appointment in most of the US.

Skin cancer detection in primary care: the state of play

There is a strong case for the benefits of PCP screening for skin cancer. There is also good evidence that it works in practice and that patients are able to access those benefits. ‘Primary care clinicians have a vital role to play in detecting and managing patients with skin lesions suspected to be skin cancer, as timely diagnosis and treatment can improve patient outcomes, particularly for melanoma,’ argue Dr. Owain T Jones and colleagues — though they note that ‘detecting skin cancer can be challenging, as common non-malignant skin lesions such as seborrhoeic keratoses share features with less common skin cancers.’

An investigation by a team including associate professor of dermatology Dr. Laura Ferris recently found that ‘PCP screening is an effective way to improve early detection of melanoma, which could potentially save lives,’ Dr. Ferris said. In particular, the study found that melanomas detected by PCPs during Dr. Ferris’ study were about half the thickness of those detected during dermatologists’ visits, meaning a better prognosis and in particular a sharply reduced risk of metastasis since thicker tumors over 1mm thick had often spread to the dermis. Only 5% of the patients whose tumors were caught by PCP screening in the study had tumors over 1 mm in thickness, compared with 20% of those screened conventionally by dermatologists.

‘The PCP screenings prevented a lot of people from needing more aggressive therapy. Additionally, we did not see a high rate of false positive biopsies, in which no skin cancer was present, nor did we see a high rate of unnecessary dermatology referrals or skin surgeries, all of which suggest that the program did not simply drive up health care costs needlessly,’ Dr. Ferris said.

Skin cancer detection: tools and methods

The Skin Cancer Foundation and the American Cancer Society recommend monthly self-examinations and annual doctor visits, where skin cancer screening is initially carried out using a naked-eye investigation of the patient’s skin. A five-point checklist for non-dermatologist clinicians to identify skin cancers was developed in the UK by Elvira Moscarella and colleagues, and is now in widespread use:

- Visible sun damaged skin on exposed areas (red and brown to black macules and crusts on visible skin);

- More than 20 nevi on the arms;

- One or more ABCD positive lesions (flat, large and asymmetric macules);

- One or more EFG positive lesions (elevated, firm and growing skin lesions);

- A pigmented lesion larger than 1.5 cm in diameter.’

Having skin visually inspected by a PCP using this five-point list improves a patient’s chances of a favorable outcome by accelerating diagnosis — though it was never intended to allow PCPs to diagnose skin cancer, but to ‘involve GPs [General Practitioners — primary care doctors and family physicians] in the selection of patients to be referred to the specialist, in order to reduce the waiting time while avoiding the risk to leave cancers untreated.’ The length and consequences of the resulting process have already been considered.

Most practices now consider ‘unaided ("naked-eye") examinations alone… insufficient.’ Dermatologist examinations are typically aided by non-invasive imaging techniques such as confocal microscopy, OCT, and total body photography to inform whether to perform biopsies. However, the most commonly-used augmentation to the naked-eye test is the dermatoscope.

(Source) A simple dermatoscope.

Widely used by dermatologists since the 1980s to diagnose and monitor skin cancers, dermatoscopes consist of a handheld light source and magnifier. The process is also known as dermoscopy, epiluminescence microscopy, incident light microscopy, and skin-surface microscopy.

(Source) Superficial spreading melanoma imaged in various ways including dermoscopy (top left).

Dermatoscopes allow clinicians to see subsurface skin structures in the epidermis and the papillary dermis, as well as the dermoepidermal junction which is a crucial corridor for melanoma metastasis. These structures are not visible to the naked eye, so dermatoscopes allow for more accurate and timely triage of serious, time-sensitive skin cancers as well as more accurate detection and diagnosis.

For this reason, Australian primary care providers typically use dermatoscopes frequently. Australia has the world’s highest incidence of skin cancers and dermoscopy is widely used by primary care providers: one study found that 49% of registrars (senior doctors) had dermoscopy training, 61% of consultations involving skin or pigmented lesion checks used dermoscopy, and dermoscopy use changed diagnoses 22% of the time and increased diagnostic confidence 55% of the time. Programs exist at the national and state level in Australia to promote the use of dermoscopy in primary care and short, practical courses for non-specialists are widely available.

In the USA, the situation is different: dermoscopy is still mainly the preserve of dermatologists — and even they underutilize it. One study found dermoscopy use rates in US dermatologists were 48% — below the rate of primary care providers in Australia, and exactly half the 96% of Australian dermatologists who regarded the tool as ‘essential.’

Using a dermatoscope effectively requires specific training, but not advanced or highly specialized training; in studies, nurse practitioners and other non-physician healthcare providers have been shown to utilize dermoscopy effectively to improve patient outcomes. The authors of a 2015 literature review even suggested that ‘laypersons in the personal care service industry whose professional duties often involve cutaneous sites, such as hair stylists, barbers, aestheticians and massage therapists… could aid in providing skin cancer screening to the general population.’ Yet this is only effective with proper training, since ‘efficacy is largely related to user skill.’

Additionally, there are currently no validated, FDA-approved image or optical-based tools available that provide any kind of skin cancer assessment to support physicians’ detection and management of suspicious lesions, as detailed in a recent JAAD skin cancer AI review paper. However, advances in new technologies, like the field of Elastic-Scattering Spectroscopy (ESS), now seem likely to change this situation, putting more of the power — and responsibility — to identify malignant lesions in the hands of primary care practitioners.

How can PCPs access the benefits of improved skin cancer detection with dermoscopy?

The case for the need for PCPs to screen for skin cancer, and the evidence that they can successfully perform screenings, both appear strong. However, PCPs need the right skills and the right tools for this to work.

In theory, a PCP may already be equipped to offer screening. However, appropriate training determines whether patient outcomes will be positively affected or remain the same. Tool selection is equally important, as the number of dermatoscope types on the market rises. Adequate training lets PCPs make the right decisions for their practices and patients. We’d always recommend seeking out a course designed by dermatologists but aimed outside the discipline, at PCPs. (One like this, which we offer, for instance.)

While the typical PCP is either not using dermoscopy at all, or using one without formal training, patients are not being provided with the best skin care. But PCPs with the right tools and skills can help short-cut long wait times and slow responses, fast-tracking patients with the most serious problems and improving their own practices’ finances and reputation.